By Mike Raita, International Motorsports Hall of Fame Executive Director

Before becoming the Executive Director of the International Motorsports Hall of Fame in July of 2020, I was a television sportscaster for the ABC affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama. In that role I had the privilege of covering the 1998 Daytona 500, which was arguably the best moment in the track’s storied history, and the 2001 Daytona 500 which was inarguably the worst. Both stories involved Dale Earnhardt.

Earnhardt, as his nickname suggested, could be intimidating. Earnhardt was the one driver I didn’t want to aggravate. My TV station covered several annual events and the races at Daytona and Talladega were among them. Even though the drivers only saw me a couple of times a year, they tended to remember me because I am bald, and bald television reporters were a very small minority. While having a unique look can, at times, work in your favor, it can also work to your detriment – like if you ever made them angry by asking a question they didn’t like.

With the style of racing at Talladega and Daytona, the tracks were a perfect place for tempers to flare. In the spring of 1998, I witnessed Dale Earnhardt lose his at Talladega. There were forty-four laps to go in the DieHard 500, and Bill Elliott and Dale Earnhardt were running side-by-side in fourth and fifth place when Ward Burton clipped Earnhardt’s car which caused Earnhardt to hit Elliott in the right rear quarter panel. The two cars got locked together and spun up the track and crashed hard into the wall. Elliott took the brunt of the impact; his car belching flames from under the hood. As the two cars slid through the tri-oval, Elliott’s car was flipped on its roof and Earnhardt’s car was on its side. Both drivers were able to walk away from their cars but Elliott was wobbly.

With the style of racing at Talladega and Daytona, the tracks were a perfect place for tempers to flare. In the spring of 1998, I witnessed Dale Earnhardt lose his at Talladega. There were forty-four laps to go in the DieHard 500, and Bill Elliott and Dale Earnhardt were running side-by-side in fourth and fifth place when Ward Burton clipped Earnhardt’s car which caused Earnhardt to hit Elliott in the right rear quarter panel. The two cars got locked together and spun up the track and crashed hard into the wall. Elliott took the brunt of the impact; his car belching flames from under the hood. As the two cars slid through the tri-oval, Elliott’s car was flipped on its roof and Earnhardt’s car was on its side. Both drivers were able to walk away from their cars but Elliott was wobbly.

Meanwhile, a sea of media rushed to the infield care center to wait on the drivers to get treated before they made their way back to the comfort of their haulers. I was there with ABC 33/40 Chief Photographer Bill Castle. Bill was very aggressive. He took a lot of pride in getting the best shot and had a knack for always being in the right spot. So, there were Bill and I, front and center, as a crowd of 30-40 members of the media waited on the drivers to come through the gate that separated us from the infield care center.

Elliott never appeared. He was whisked away to his airplane which would fly him home where he would receive treatment for a bruised sternum. None of the local crews covering the race adhered to the etiquette of allowing the network broadcasting the race to have first access to the drivers. So, as Earnhardt, with his wife Teresa slightly behind him, made one or two steps through the gate, everyone converged on them. We did allow ABC reporter Bill Weber to ask the first question which was, “First of all Dale, how are you?” The response was classic Earnhardt, “Hot,” was all he said. Then he spun around to go back into the safety of the care center and as he did, his wife got tangled up with Bill. The noise she made wasn’t quite a scream, but it was more than a gasp and loud enough for Earnhardt to hear. Earnhardt whipped around and threatened Bill and everyone else in the crowd, “Touch my wife again and I’ll whup all of you.”

The ABC network crew was allowed through the gate and conducted the only interview Earnhardt gave after that race, with Earnhardt explaining, “Fire came off Elliott’s car and burned my hair, singed my mustache off a little bit. I’m going to have to grow some new ones,” he said. Again, quintessential Earnhardt.

Earnhardt was both a pain and a pleasure to cover. His gruff exterior and no-nonsense approach with the media made getting comments from him difficult. I was there in 1998 when he won the Daytona 500. It was brilliant. Finally, the driver who was arguably the best the sport had ever known won the series’ biggest race. After Earnhardt took the checkered flag and made his cool down lap, he drove down pit road where all the other crews had gathered to congratulate him. After that, he turned his car into the infield and began doing donuts.

ABC 33/40 sports photographer Chris Lupenski had left me to go get video of whatever celebration he could. After Earnhardt did his media obligations in victory lane, Lupenski and I met back at our satellite truck to start putting together a plan for our coverage for the newscasts. Chris was about to burst with pride, saying over and over again that he’d gotten the ‘money shot.’ Chris explained that while Earnhardt was doing donuts, he was about as close to Earnhardt’s car as anyone could get. He told me he was holding the camera down low in order to get the full effect. I was excited and couldn’t wait to see it. When Chris put the tape into the tape deck, we saw Earnhardt cross the finish line, we saw his crew celebrate, we saw him drive his car down pit road and then … nothing until Earnhardt got to victory lane. Video cameras have a button that you push when you want to record. The same button stops the recording. Sometimes a ‘double-click’ occurs; you think you’re rolling tape, but you’re not because as soon as you clicked the button to record, you inadvertently clicked it again to stop the recording. That’s what happened to Chris. I never let Chris live it down, and as time passed, we laughed about it a lot but on that particular day, there was nothing funny about it. Chris was really disappointed. So was I.

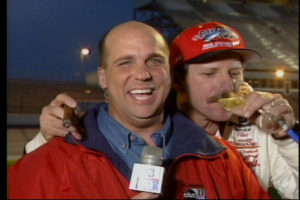

As gruff and cantankerous as he normally was with the media, after his Daytona win, Earnhardt was more than happy to do one-on-one interviews with about seven television crews that had stuck around and waited him out through all of the other post-race obligations that go along with winning the Daytona 500. Chris and I were one of those crews. Smoking a cigar and holding a glass of champagne with his arm around me, it is an interview I will never forget. As I wrapped it up and congratulated him on his win and thanked him for his time, The Intimidator rubbed my head. I felt special.

As gruff and cantankerous as he normally was with the media, after his Daytona win, Earnhardt was more than happy to do one-on-one interviews with about seven television crews that had stuck around and waited him out through all of the other post-race obligations that go along with winning the Daytona 500. Chris and I were one of those crews. Smoking a cigar and holding a glass of champagne with his arm around me, it is an interview I will never forget. As I wrapped it up and congratulated him on his win and thanked him for his time, The Intimidator rubbed my head. I felt special.

I was back at the Daytona International Speedway in 2001. This was the fifth straight Daytona 500 I would cover, and our coverage, as it had the previous four years, included stories on local drivers and crew members, interviews with the favorites, and local happenings at the track including Valentine’s Day weddings. A good week looked like it would culminate with a great finish. On the final lap, Michael Waltrip was leading Dale Earnhardt Jr. with Junior’s dad just behind him in third place.

Of course, we all know how it ended. I have had to cover difficult stories, but without question the two most difficult involved racing – the deaths of Davey Allison and Dale Earnhardt. When an event as big as that one occurred, I felt a responsibility to provide the absolute best, most comprehensive coverage that I could. Earnhardt was such a popular driver and had so many fans who were profoundly affected by what happened that day. I felt obligated to not simply provide the facts of what happened that day but to also capture the emotion at the track.

ABC affiliates from all over the southeast called and requested live reports from me for their newscasts that evening. I put together two taped reports, one for the stations I was helping and one for ABC 33/40. The story I did for the stations I was helping aired without a hitch. Unfortunately, in my haste to get everything finished under a tight deadline, I forgot to cover some of my audio with video, and so for about six seconds, color bars were on TV in the Birmingham market. That was deeply disappointing.

ABC affiliates from all over the southeast called and requested live reports from me for their newscasts that evening. I put together two taped reports, one for the stations I was helping and one for ABC 33/40. The story I did for the stations I was helping aired without a hitch. Unfortunately, in my haste to get everything finished under a tight deadline, I forgot to cover some of my audio with video, and so for about six seconds, color bars were on TV in the Birmingham market. That was deeply disappointing.

In television newsrooms, you will usually find that most reporters and anchors have morbid senses of humor. Maybe it’s because death and carnage are such a big part of what they report on and joking about it takes the edge off, or maybe it’s because they’re just twisted. Before a race when the drivers are making their way to their cars is a great time to get unobstructed video and close-ups. We called those hero shots. The guys don’t have their helmets on as they hang out around their cars with their wives or girlfriends.

Videographers tried to be creative with this video. They would start the shot on a driver’s feet and tilt up to his face. They would start the shot on the rear bumper and walk along the side of the car showing all of the sponsor decals and the number on the side of the car before ending the shot on the driver’s face. It’s not the most compelling video but it was great file video that we could use any time one of the drivers made news. As Jeff Myers and I debated whether we needed to get some hero shots before the 2001 Daytona 500, I flippantly told him that we had better get it just in case one of these knuckleheads ends up in the hospital. I had no idea what would happen that day. After that I would cover many more races, but I never made that comment again.

Twenty years later, Earnhardt’s legacy lives on in the International Motorsports Hall of Fame which houses one of his cars, motorcoach, and many personal photos. Inducted in 2006, Earnhardt still remains one of the sports most popular drivers, and his display commands attention from all who visit.